Toxic Green Tides of Brittany

The French region of Brittany has been experiencing green algal blooms for decades. Environmentalists decry the inefficient management of pollution by authorities.

Credit: Jelena Prtorić

“I was the second most beautiful baby in the local hospital in 1945.” Over the years, André Ollivro, 77, has learnt how to put on a show for journalists. He opens with a personal story, lines up the anecdotes of his life, with a scrapbook full of news clips he’s featured in as a prop, and readily poses for the camera. Dressed in dark blue overalls, a blue and white striped T-shirt, and a red cap, he looks like the epitome of a Breton man one might see on the cover of a local tourist guide. Ollivro has become somewhat of a local legend despite himself, by virtue of fighting the pollution on his doorstep. He spends his summers in a white-painted bungalow above the beach of Grandville, in the Northwestern part of France, which has been covered by a mass of green algae every summer for decades.

The green algae is a sea lettuce native to the region that gets washed ashore amid tide changes and waves. But since the 1970s, the presence of the piles of decomposing algae, smelling of rotten eggs, on the beaches has become a scourge for the region, and – according to Ollivro, other activists, and scientists – constitutes a serious public health issue.

When the seaweed starts decaying, it emits hydrogen sulphide, a gas that can, depending on the concentration and duration of exposure, trigger headaches or eye irritation, provoke unconsciousness, or even cause death. Over the years, a number of animal deaths – wild hogs, dogs, and a horse – have been linked to the poisonous gas emanating from the seaweed. Moreover, six human deaths have been linked to the presence of algae, although the causal link still hasn’t been fully established due to the lack of tests performed.

Region feeding France

Today, the blooming of algae in Brittany is linked to an increased input of nitrates from fertilisers and manure entering the small waterways running through dense agricultural areas, flowing to the sea. The issue of the excessive input of nitrates has been a long-standing issue. In 2001, the European Court of Justice condemned France for breaching the Nitrates Directive regarding the levels of nitrates in some river basins in Britanny; in 2004, the country was condemned for not designating certain areas as Nitrate Vulnerable Zones; and in 2014, France was condemned once again for breaching the Directive.

The green tides usually occur in shallow bays, where the slow renewal of the coastal water results in the retention of nutrients. The tides are more intense in periods of greater sunlight, between mid-May and September.

Credit: Credit: Jelena Prtorić

After World War II, Brittany transformed from a region of small farming plots to a leader in livestock farming in France, feeding “one out of three French citizens.” More than 60 % of the regional territory is used for agriculture, and the region is the leader in egg and pork production in the country. It is also one of the leading regions for vegetable production in the country.

In his book Green Tides: 40 keys to understanding, scientist Alain Ménesguen explains how the presence of algae in Brittany intensified after World War II, along with the development of high-intensity agriculture. In 1971, pollution by green algae was mentioned for the first time in an official capacity, in the municipal council of Saint-Michel-en-Grève. In that year, over the course of ten days in June, 6600 cubic metres of algae were amassed. In the period 1997–2018, the volume of algae amassed annually did not drop below 25,000 cubic metres.

“When I retired at the age of 51 and came back to Brittany, it wasn’t the same scenery that I could remember from my childhood. Agriculture had evolved and changed the landscape in the process,” he says. He soon became the president of the organisation Halte aux Marées Vertes (Stop the Green Tides), which has fought pollution from green algae ever since. The organisation has filed lawsuits against the French state for not protecting its citizens, and organised mass protests to stop the expansion of mass farms and the building of biogas plants operated using animal manure.

When the algae season starts, Ollivro, a former gas technician, can often be seen with his gas mask and a hydrogen sulphide monitor on the beach, measuring the gas levels.

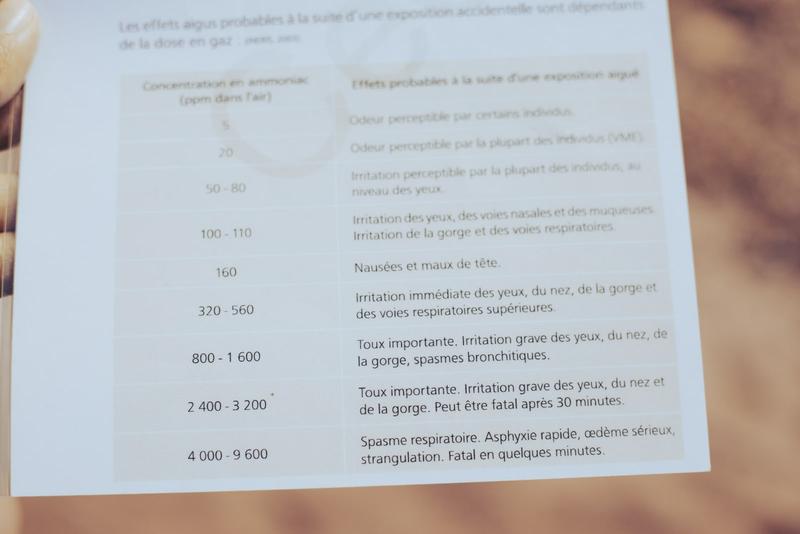

On July 21 2022, his machine starts beeping as soon as Ollivro steps into what looks like a pile of brown mud but is, in fact, decomposing algae. The beeps indicate the presence of hydrogen sulphide. The levels hover around 40–50 parts per million (ppm), which, according to a chart that Ollivro is carrying with him, can produce a “noticeable odour” and “palpable irritation of the eyes.” Headaches and nausea start at 160 ppm. At levels above 2400 ppm, the gas can be deadly, depending on the amount of time spent inhaling it.

Credit: Jelena Prtorić

Credit: Luisa Izuzquiza

The mere presence of algae provokes a disbalance in flora and fauna. Animals flee seas overburdened with algae because of the consequent oxygen depletion, while the degradation of algae on the beach results in a decimation of the number of animals, mostly invertebrates, living in shore waters. However, in July 2008, the pockets of hydrogen sulphide from the decomposing algae were linked to the deaths of two dogs. A year later, a horse was found dead on one algae-polluted beach. In July 2011, at least 31 wild boars were found dead on a muddy, algae-covered beach. The deaths of two joggers, one in 1989 and another in 2016, a diver working on algae pickup entering a coma in 2018, and the death of another are all thought to be connected to the hydrogen sulphide.

Credit: Jelena Prtorić

Agricultural omerta

In her book Green Algae: The Untold Story, French journalist Inès Leraud traces algae pollution and the issues surrounding it across decades. Leraud notes that Joel Kopp, a scientist from the French Institute ISTPM (now IFREMER, French Research Institute for the exploitation of the sea) concluded in 1977 that coastal pollution is caused by agriculture. In parallel, Leraud explains how the agricultural lobby has tried to silence the scientists and activists, and has lobbied the local authorities in order to be able to continue business as usual. And sometimes, some of them have resorted to threats.

In front of his bungalow, Ollivro lays down photos and documents outlining his struggle against green algae pollution over the past two decades and the issues this struggle has brought him. There were menacing emails, insults directed towards him on the street, a pile of manure dropped in front of his house, a firecracker that destroyed his letter box, a dead fox left in front of his door.

The agricultural community has long disputed the connection between excessive nitrates and algal bloom. In 2011, when the beach of Morieux was closed after the death of 36 wild boars, the FNSEA, a French umbrella organisation charged with the representation of local and regional agricultural unions, organised a football game on the beach to show that there was nothing to fear. Today, they do not contribute to the cost of cleaning up the algae on the beaches, and they fought taxation of nitrate exceedances on the basis of the polluter pays principle in the bill on water of 2002, as Alain Ménesguen recalls in his book.

Credit: Jelena Prtorić

Accountability of the state

By now, the link between excessive nitrates and algal bloom has been confirmed by a number of scientists, environmental organisations and court decisions. However, Brittany’s water agency didn't admit this until the end of the 1990s, while the government waited until 2010.

The tide has turned since 2010. Today, the local authorities measure the levels of gas on the beaches, and close them to the public in cases of massive algae presence. They also have an obligation to pick up algae deposits on the beaches, and store them in disposal centres, where they are dried. The State and the local authorities spend about €1 million per year cleaningup the algae.

The French government has also passed two action plans for fighting green algae, in 2010, and 2016. In 2021, the French Court of Auditors objected that both plans had “ill-defined objectives and uncertain effects on water quality,” a lack of sufficient funding for the measures, and a lack of consistency with other agricultural and agri-food policies.

“The problem with these action plans is that they don’t aim to reduce the inputs, but only the nitrate leakage. Moreover, they are mostly targeting animal manure, and disregarding the inputs from mineral fertilisers,” explains Estelle Le Guern, lead of the research unit on water and agriculture with Eau and Rivières (Water and Rivers), an NGO that has been working on the protection of regional waterways since the 1960s. “When we look at the data, we see that the pollution by nitrates has progressed, so there is a discrepancy between the law and the situation in the field. The law is curative, so it doesn’t prevent pollution,” she adds.

In 2022, Eau and Rivières filed two lawsuits against the French state in the Rennes administrative court. The NGO estimated that the state didn’t act adequately to curb the pollution, and estimated the damages – due to beach closures and cleaning activities – to be €3.2 million. This happened as the third Green Algae Fighting Plan was announced. The NGO denounced it as “not concrete enough” and deplored the lack of “sufficient funds.”

Environmental organisations also continue the fight – in a different way. Today, the NGO Stop the Green Tides has a new co-president, Annie le Guilloux, who continues the fight that Ollivro started. Le Guilloux, born and raised in the region of Saint Brieuc, the region with the most acute algae pollution, explains that current measures promoted by the government aren’t enough, and are confusing for the farmers themselves. “There are tables defining what the width of a buffer zone next to a waterways needs to be, depending on the slope of the agricultural slot and its length. This is an example of how we keep adding more and more complicated measures that produce only cosmetic changes,” she says.

Today, despite us living in the age of omnipresent information, she believes that people are still not aware of the amplitude of the problem.

“You can’t fight the green tides without questioning the agricultural system. And doing that means to engage in politics – even if you’re not belonging to a certain party or political movement,” she says. Today, they join forces with other environmental organisations, such as Extinction Rebellion. In the summer of 2022, they started a joint campaign to raise public awareness among beachgoers of the issues surrounding green algae. Le Gouilloux believes that young blood is needed, as many feel defeated after years of struggle. “We, who have been fighting for a long time, need to work with younger groups such as Extinction Rebellion. I have experience, but I am not able to climb the building of a local government to put up a banner, which is what they did in one of the last protests. And we need more spectacular actions like that if we want to interest younger generations in this issue,” Le Guilloux concludes.